Build a Slack Clone with an API Gateway WebSockets API

See the full example on GitHub

In a previous blog post I walked through the process of creating a Next.js application with a very simple WebSocket connection for streaming updates from the server. In that post, I explained that the task of running your own WebSocket-capable server might be a burden for some people, especially if you have a mostly serverless deployment model.

So I got to thinking, "Is there a way to run a WebSocket-based service in a serverless way?" There are SaaS vendors that offer real-time messaging as a service, like Ably and Pusher. But I was especially interested in AWS' API Gateway WebSockets API product, which offers a serverless WebSocket broker with a lot of options for developers to customize how those WebSocket connections fit in to the rest of their application.

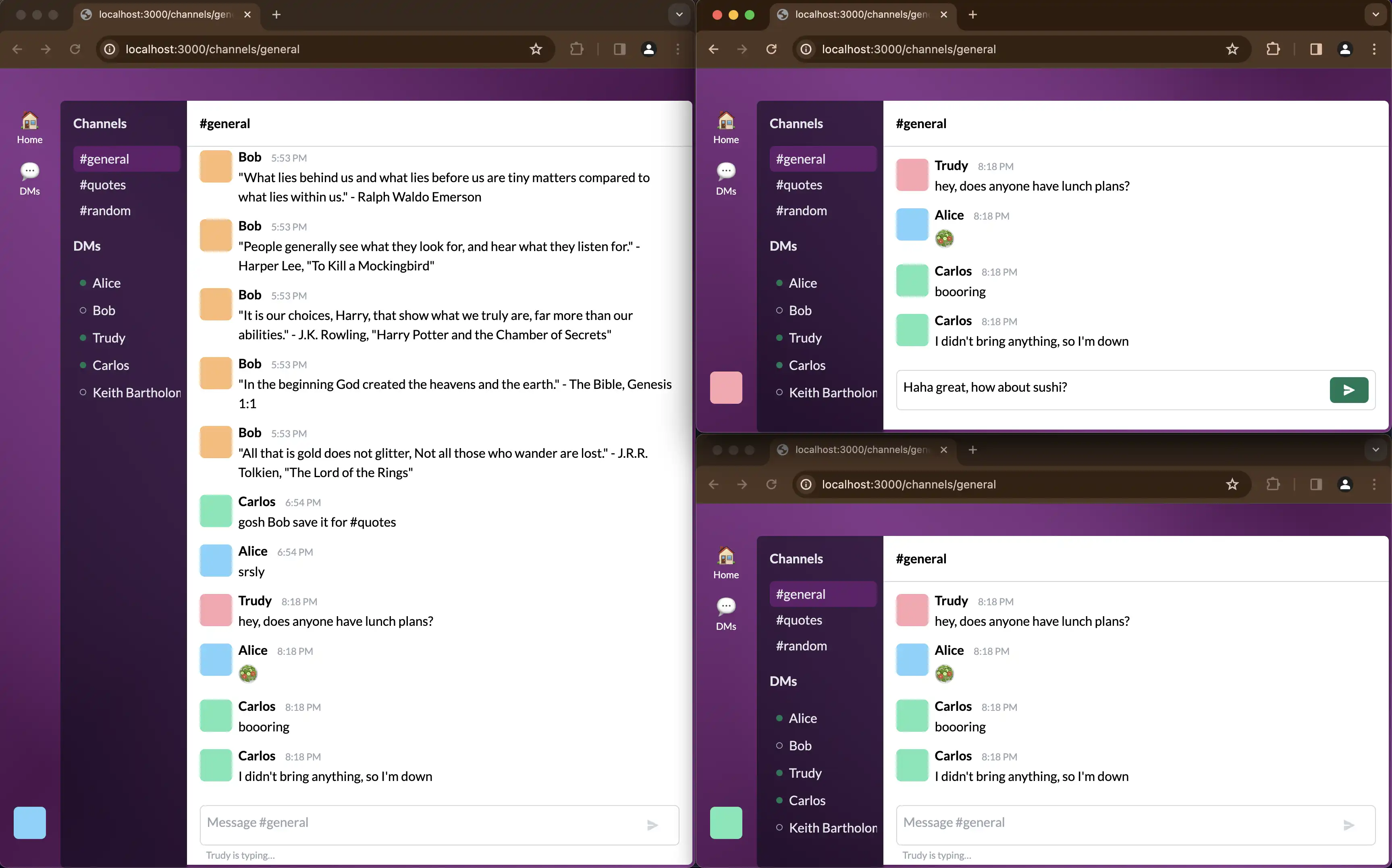

I decided to build a clone of Slack to demonstrate some real-world communication scenarios using only API Gateway, Lambda, and DynamoDB.

Overview

The demo consists of a front-end Next.js app that makes a WebSocket connection to an API Gateway WebSockets API and uses that to stream updates about messages, when users are typing, and which users have an active connection.

The WebSockets API forwards every request to one of two Lambda functions. One handles when clients connect and disconnect, and the other handles all other application events. Dividing this work between two Lambdas was an arbitrary choice I made; you might choose to split work between more functions if each of your API operations has different scaling needs. Conversely, you might choose to keep API operations combined into a single Lambda to improve your cold-start ratio.

Each Lambda stores state in a DynamoDB table, which stores long-term information about channels and users, and also stateful information about the ephemeral WebSocket connections that are currently open. Depending on the API operation, these Lambdas will also publish events to relevant WebSocket connections. They do this inbound and outbound communication directly; A more advanced application might choose to decouple these tasks by publishing an event to an event bus, then letting a separate task handle the outbound communications.

Create the infrastructure

TL;DR: do everything in this section by running npm ci && npm run publish in the demo repo.

I've created a couple CloudFormation templates to provision everything this demo needs, but I'll walk through some of the resources one-by-one to explain them.

-

Prep step: Create an S3 bucket for Lambda assets.

These resources aren't really part of the demo itself, but make deploying it easier. I created an S3 bucket into which I can write Lambda code as ZIP files, and record the name of the bucket in AWS Systems Manager Parameter Store.

S3Bucket: Type: AWS::S3::Bucket Properties: AccessControl: Private VersioningConfiguration: Status: Enabled LifecycleConfiguration: Rules: - Id: DeleteOldVersions Status: Enabled NoncurrentVersionExpirationInDays: 30 AbortIncompleteMultipartUpload: DaysAfterInitiation: 7 Parameter: Type: AWS::SSM::Parameter Properties: Name: !Sub /${ProjectName}/s3-bucket Type: String Value: !Ref S3Bucket -

Build and upload the Lambda code.

Bundle, zip, and upload the code for each of the Lambda functions we're about to create.

npm -w packages/test-connect run build && npm -w packages/test-connect run upload npm -w packages/test-default run build && npm -w packages/test-default run uploadThese npm scripts use

esbuildto bundle the handler code into a single file, compresses that file into a.zipfile, then uploads the.zipfile to S3. When bundling withesbuild, I specify--external:@aws-sdk*to omit the AWS SDKs from the bundle, because those packages are already globally available as part of thenodejs20.xLambda runtime. -

Create the DynamoDB table.

This table uses

pkandskas its primary key and sort key fields, respectively. This is to accommodate the single-table design pattern which I'll explain more later. I'll also create an inverted index to support a variety of relational queries. (In the inverted index,skis the partition key andpkis the sort key, thus inverting the main index pattern)DynamoDBTable: Type: AWS::DynamoDB::Table Properties: TableName: !Ref ProjectName BillingMode: PAY_PER_REQUEST KeySchema: - AttributeName: pk KeyType: HASH - AttributeName: sk KeyType: RANGE GlobalSecondaryIndexes: - IndexName: sk-index KeySchema: - AttributeName: sk KeyType: HASH Projection: ProjectionType: ALL - IndexName: conn KeySchema: - AttributeName: conn KeyType: HASH Projection: ProjectionType: KEYS_ONLY AttributeDefinitions: - AttributeName: pk AttributeType: S - AttributeName: sk AttributeType: S - AttributeName: conn AttributeType: S TimeToLiveSpecification: AttributeName: ttl Enabled: trueI've also created an index on the

connattribute to support pruning connection records when a user disconnects, and a time to live on thettlattribute to prune messages that are over a day old. I'm only doing the TTL thing to avoid growing storage costs for the demo; you could easily allow DynamoDB to store multiple terabytes worth of messages, or implement a tiered storage system that migrates older messages to S3 when they reach a certain age. -

Create the (empty) API Gateway.

There's not a lot to do to make an API Gateway on its own. This is only an empty API and production stage, and I'll associate more resources with it later.

ApiGateway: Type: AWS::ApiGatewayV2::Api Properties: Name: !Ref ProjectName ProtocolType: WEBSOCKET RouteSelectionExpression: "$request.body.event" ApiGatewayStage: Type: AWS::ApiGatewayV2::Stage Properties: ApiId: !Ref ApiGateway StageName: production AutoDeploy: true DefaultRouteSettings: ThrottlingRateLimit: 10 ThrottlingBurstLimit: 100 StageVariables: DYNAMODB_TABLE_NAME: !Ref DynamoDBTableI'm configuring the API Gateway to parse each incoming request as JSON and to use the

eventproperty of that message to route requests. I'm also configuring the deployment stage to limit clients to about 10 requests per second, while allowing temporary bursts above that limit. I'm pretty sure that limit is applied per connection and not to all connections in aggregate. -

Create an IAM role for the Lambda handlers.

Both Lambdas will share the same IAM role, which has policies that allow it to write its logs to CloudWatch Logs (a basic Lambda requirement), write traces to AWS X-Ray, and to do the necessary read/write operations in DynamoDB and API Gateway.

LambdaRole: Type: AWS::IAM::Role Properties: RoleName: !Sub ${ProjectName}-lambdas AssumeRolePolicyDocument: Version: "2012-10-17" Statement: - Effect: Allow Principal: Service: - lambda.amazonaws.com Action: - sts:AssumeRole Policies: - PolicyName: "LambdaBasicExecution" PolicyDocument: Version: "2012-10-17" Statement: - Effect: Allow Action: - logs:CreateLogGroup Resource: !Sub "arn:aws:logs:${AWS::Region}:${AWS::AccountId}:*" - Effect: Allow Action: - logs:CreateLogStream - logs:PutLogEvents Resource: - !Sub "arn:aws:logs:${AWS::Region}:${AWS::AccountId}:log-group:/aws/lambda/${ProjectName}*:*" - Effect: Allow Action: - xray:PutTraceSegments - xray:PutTelemetryRecords Resource: "*" - PolicyName: "ResourceAccess" PolicyDocument: Version: "2012-10-17" Statement: - Effect: Allow Action: - dynamodb:Query - dynamodb:Scan - dynamodb:GetItem - dynamodb:PutItem - dynamodb:UpdateItem - dynamodb:DeleteItem - dynamodb:BatchGetItem - dynamodb:BatchWriteItem Resource: - !GetAtt DynamoDBTable.Arn - !Sub "${DynamoDBTable.Arn}/index/*" - Effect: Allow Action: - execute-api:Invoke - execute-api:ManageConnections Resource: !Sub "arn:aws:execute-api:${AWS::Region}:${AWS::AccountId}:${ApiGateway}/*/*/*" -

Create the Lambda handlers and supporting resources.

I'll create a log group with a conservative retention policy (again, trying to control costs) and then create the Lambda function itself. After that, I'll create a resource policy to allow API Gateway to invoke the Lambda, and register the Lambda function as an "integration" with API Gateway, so it can be used with a variety of routes.

ConnectLogGroup: Type: AWS::Logs::LogGroup Properties: LogGroupName: !Sub "/aws/lambda/${ProjectName}-connect" RetentionInDays: 7 ConnectLambda: Type: AWS::Lambda::Function Properties: FunctionName: !Sub ${ProjectName}-connect Handler: index.handler Runtime: nodejs20.x Architectures: - arm64 TracingConfig: Mode: Active MemorySize: 1800 Role: !GetAtt LambdaRole.Arn Code: S3Bucket: !Ref AssetBucketName S3Key: connect.zip Environment: Variables: TABLE_NAME: !Ref DynamoDBTable LoggingConfig: LogGroup: !Ref ConnectLogGroup ConnectPermission: Type: AWS::Lambda::Permission Properties: Action: lambda:InvokeFunction FunctionName: !Ref ConnectLambda Principal: apigateway.amazonaws.com SourceArn: !Sub "arn:aws:execute-api:${AWS::Region}:${AWS::AccountId}:${ApiGateway}/*/*" ConnectIntegration: Type: AWS::ApiGatewayV2::Integration Properties: ApiId: !Ref ApiGateway IntegrationType: AWS_PROXY IntegrationUri: !Sub "arn:aws:apigateway:${AWS::Region}:lambda:path/2015-03-31/functions/${ConnectLambda.Arn}/invocations" IntegrationMethod: POST PayloadFormatVersion: "1.0"There's a lot going on there:

- I'm manually creating the log group so that I can control its retention policy. If I didn't do this, AWS would create a log group automatically, but that log group would be configured to store all its logs forever and would not be deleted after I delete the other resources.

- I'm using the

arm64(AKA "Graviton") architecture for the better price-performance, and because I have no x86-specific dependencies. - I'm setting the function memory to 1,800 MB in order to be slightly above the magic threshold of 1,769 MB at which Lambdas have 1vCPU of compute capacity.

- The wildcards when configuring API gateway permissions are a little opaque to me; GitHub Copilot helped me write them and I'm honestly not sure how I would have arrived at the correct values on my own.

-

Register the Lambdas with API Gateway routes.

The

ConnectIntegrationresource I created before doesn't actually modify the API Gateway API; it only indicates that the Lambda is available as an integration. I'll make routes for each API operation that I want to associate with one of the Lambdas.ConnectRoute: Type: AWS::ApiGatewayV2::Route Properties: ApiId: !Ref ApiGateway RouteKey: $connect Target: !Sub integrations/${ConnectIntegration} DisconnectRoute: Type: AWS::ApiGatewayV2::Route Properties: ApiId: !Ref ApiGateway RouteKey: $disconnect Target: !Sub integrations/${ConnectIntegration} SendMessageRoute: Type: AWS::ApiGatewayV2::Route Properties: ApiId: !Ref ApiGateway RouteKey: sendMessage Target: !Sub integrations/${DefaultIntegration}For each route,

RouteKeycorresponds to either the$connector$disconnectdefaults built in to API Gateway, or to the value of theeventproperty in the request body.

DynamoDB data model

The application uses a single DynamoDB table that leverages the single-table design pattern. In single-table design, you overload the DynamoDB partition and sort keys to allow them to represent multiple collections of items, as well as relationships between items. I do this by including additional information about the type of item being represented in the pk and sk columns. For example, I have a record like {"pk": "ROOM#general", "sk": "ROOM"} that represents a chat room itself, and additional records like {"pk": "ROOM#general", "sk": "USER#<userId>"} that represent each user that has joined the room. The general pattern that I followed is that records like {"pk": "THING#<id>", "sk": "THING"} represent the thing itself along with its metadata, and records like {"pk": "THING#<id>", "sk": "RELATION#<id>"} represent an item related to the original thing.

Following the single-table design pattern, I have two generic columns named pk and sk that correspond to the primary key and sort key, respectively. I also created an inverted index named sk-index that allows me to query on the sk column directly, which helps me make a variety of queries to list the items related to another item.

As of this writing, I have a fairly large mistake in my data model. The main purpose of single-table design according to Alex DeBrie's writing is to avoid making multiple, serial calls to get a whole set of related data (this is basically Dynamo's version of SQL joins). Unfortunately, that's exactly what my app is doing. This is because I'm only storing foreign keys in most records and then making additional queries to look up the related items.

If I get around to it, I'll fix this by including more data about the related entities in the item itself.

Rooms

Much of the data model revolves around rooms, which I use to represent both channels and DMs. I also need to know which users, WebSocket connections, and messages are associated with each room.

| pk | sk | conn | message | ttl | user |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROOM#general | ROOM | ||||

| USER#abcdefghijkl | |||||

| CONN#Q000000000 | CONN#Q000000000 | ||||

| MESSAGE#1703806209644 | Hello, world! | 1703892609 | USER#abcdefghijkl |

This model supports the following access patterns:

- List rooms (

SELECT * FROM "table"."sk-index" WHERE sk = 'ROOM') - List all users in a room (

SELECT * FROM "table" WHERE pk = 'ROOM#general' AND begins_with(sk, 'USER#')) - List all WebSocket clients subscribed to a room (

SELECT * FROM "table" WHERE pk = 'ROOM#general' AND begins_with(sk, 'CONN#')) - List all messages in a room (

SELECT * FROM "table" WHERE pk = 'ROOM#general' AND begins_with(sk, 'MESSAGE#'))

Direct messages are rooms just like any other. Their IDs are generated by sorting and then concatenating the user IDs of each member in the conversation, like ROOM#<userId1>#<userId2>. I'm not currently enforcing any permissions to prevent third parties from reading the messages in a DM. 😬

Users

Users are persistent entities, and I use their records to track things like persistence (the last time they were seen) and rate-limiting (to ensure they aren't spamming messages). The user collection is also a handy place to record a list of the WebSocket connections open for that user so I can notify the user of certain events.

| pk | sk | handle | presence | sendMessageLimit | sendMessageTtl |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USER#abcdefghijkl | USER | alice | 1703806209 | 58 | 1703806269 |

| CONN#Q000000000 |

This model supports the following access patterns:

- Get details about a specific user (

SELECT * FROM "table" WHERE pk = 'USER#abcdefghijkl' AND sk = 'USER') - List all users (

SELECT * FROM "table"."sk-index" WHERE sk = 'USER') - List all WebSocket connections for a given user (

SELECT * FROM "table" WHERE pk = 'USER#abcdefghijkl' AND begins_with(sk, 'CONN#'))

Lambda handlers

All of the business logic of the demo is handled by two Lambda functions. One handles when WebSocket clients connect and disconnect, and the other handles every other message sent over an active connection.

Handling connections

API Gateway has two built-in events, $connect and $disconnect, to handle new connections and terminating connections, respectively. I have the Lambda at packages/test-connect handle both of these. The event payload includes event.requestContext.eventType which is either CONNECT or DISCONNECT, so the function is able to handle each type differently.

The connection Lambda does extremely primitive authentication—it looks for any value in either an Authorization header or an ?authorization query string. It does no validation to determine whether that is a valid authorization token. The only purpose of this "authorization" is to identify which user has connected. After all, it's just a demo!

When a user connects, the connection Lambda adds items to DynamoDB with the user's connection ID for every room the user has joined. This makes it easier for other event handlers to quickly identify all the connections that are currently subscribed to any given room.

When a user disconnects, the Lambda looks for every record of that connection's ID and deletes it from DynamoDB so that future events stop being sent to it. (Trying to send messages to a closed connection fails pretty gracefully, but it's not very efficient to try to send messages that we know will fail)

Handling incoming messages

After a user connects, they are able to send and receive messages on the open connection. Each of these messages looks something like {"event": "sendMessage", "detail": {} }. The event property is required so that API Gateway will accept and route the request to the Lambda, and contents of the detail property will vary depending on the value of event.

Some of the message types (like listRooms and listUsers) follow a request/response cycle and would work fine in a REST API; I just didn't want to create a second API for this purpose. Each of the event types is just handled by a big switch statement:

joinRoom: Creates a record indicating that a user would like to subscribe to messages in a room. Notifies other users in that room that a new user has joined.listMessages: Lists all messages in a room. Used to retrieve the message history when a user first opens a room in their app.listUsers: Lists all users and their presence status. Used to retrieve the current presence status for all users.sendMessage: Sends a message to a room. Notifies all users in that room of the received message.updatePresence: Updates the timestamp at which the user was last actively connected. The app sends this message every minute or so as long as it's connected. Other users may observe this value and show the user as "away" if the presence timestamp is too old. Notifies all users in all rooms of the received message.userTyping: Indicates that a user is composing a message. Notifies all users in the relevant room of the received message.

Sending messages to clients

Because my Lambda functions aren't actually handling WebSockets directly, they don't communicate back to clients via a direct method like WebSocket.send(). Instead, API Gateway exposes an HTTP endpoint that my application can POST a message to, and API Gateway will forward that message to the client. This endpoint has a URL like

https:////@connections/

Each message includes the client's connection ID at event.requestContext.connectionId, so sending responses directly back to the client is pretty straightforward. However, to broadcast a message to other clients (like when notifying them of a new message), I have to look up the relevant connection IDs from DynamoDB.

The @connections endpoint is secured by IAM authorization, meaning I have to sign each request with AWS Signature v4 using the aws4 npm package.

Test the WebSocket API via the CLI

This is an optional step, but was a very helpful way for me to understand exactly what the WebSocket API was doing, and to debug the behavior of each Lambda handler as I was developing them. It requires the wscat utility.

wscat --connect $(aws ssm get-parameter --name /serverless-slack-clone/websocket-url --query Parameter.Value --output text)

> {"event": "joinRoom", "detail": {"room": "general"} }

wscat lets you type and send messages on a WebSocket connection and to see responses emitted by the API. In this demo, every message has event and detail properties, in which event indicates what type of operation is being done and detail includes open-ended details about the operation. The available event types are defined in the demo repo.

Cost

I built this demo over the course of about a week, and the whole thing cost me exactly $0.10. Most of that cost came from a few times where I turned on an automated chat bot and sent myself and three other WebSocket clients 1,500 messages/minute for several minutes. (I implemented rate limiting shortly after)

In this demo, my Lambda usage fell under the AWS Free Tier and so cost $0. Without the free tier, my Lambda usage for this demo would cost an additional $0.12.

As with many serverless products, this is free/cheap to run at small scale, but could run into surprise costs at large scale. For WebSockets APIs, API Gateway charges for both connection minutes and messages sent. If you had 1,000 clients connected 24/7, your cost for simply keeping those connections open would be $10.95. If you add to that a fairly conservative 3,000 messages sent per minute (say, if each client was sending a ping every 20 seconds), then the cost quickly climbs to $142.35, including the connection costs.

Although you only pay for what you use, the price you pay scales directly with how heavily-used the service is. This could be problematic if you have a large number of users or a very chatty application. If real-time communication is the core of your business, you might be better off building a more serverful system that's less elastic but more predictable.